How do I know if I have PCOS? Traditionally we have stated that the incidence of PCOS in women of childbearing age is between 5-10%. The definition of what constitutes PCOS has changed over the past two decades. In 1990 the National Institutes of Health defined PCOS as:

1. Irregular or absent periods

2. Increased male hormone levels (i.e., acne, facial hair)

3. No other health condition which could be causing the symptoms

In 2003, specialists in PCOS from the Eastern Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine met together. Their consensus statement, issued from Rotterdam, put forward a different definition for PCOS:

A woman could be considered to have PCOS is she had any two of these characteristics:

1. Irregular, or absent periods

2. Increased male hormone levels

3. Multiple small ovarian cysts (“string of pearls”) visualized on pelvic ultrasound

Using this second definition, a recent study of 728 Australian women by March and colleagues (2010) found an incidence of PCOS of about 18%! If the earlier NIH criteria were applied to these same women, the incidence of PCOS was about 9%. This group of women aged 27-34 were selected from birth records of a single maternity hospital. Of these community based women identified as having PCOS, some 70% did not have a prior diagnosis of PCOS.

While there are some methodology problems with this study (e.g., not every subject consented to having the ultrasound exam of their ovaries) I really like this study for two reasons. First, it really highlights the differences in incidence depending upon which definition of PCOS is used. Second, it suggests that the incidence of undiagnosed women may be much higher than we had imagined.

How do I know if PCOS is the cause of my inability to get pregnant?

Obviously there are numerous factors which can impact fertility. One can have blockage of the fallopian tubes. The male partner can have a low sperm count.

Obviously there are numerous factors which can impact fertility. One can have blockage of the fallopian tubes. The male partner can have a low sperm count.

One of the major causes of infertility in women is lack of frequent, regular ovulations. Problems with ovulations, as evidenced by irregular or absent menstrual periods, are a hallmark of PCOS no matter which definition is used.

Among PCOS women who are trying to conceive, lack of ovulations is the most common cause of below normal fertility (Thessaloniki ESHIRE/ASRM, 2008). So if nonovulation has been determined by basal body temperature charting, ovulation predictor kits, or by the presence of very irregular cycles, chances are high that PCOS may be part of the problem.

As you might have guessed, based upon the diverse definitions of PCOS, there is no single test which can diagnose PCOS. Blood tests to rule out other causes of nonovulation can include those for thyroid (TSH) and pituitary function (prolactin).

Documentation of increased male hormone levels can be done with blood tests for testosterone, sex hormone binding globulin, or a free androgen index. A pelvic ultrasound may be used to look for multiple small ovarian cysts.

Because of the linkages between PCOS and increased risks for type 2 diabetes, an overweight woman may also give blood for a glucose tolerance test. Women with PCOS convert to impaired glucose tolerance at a younger age (Ehrmann, 1993). While an abnormal glucose test result is not diagnostic for PCOS, it can suggest increased risks during pregnancy. Women with PCOS have a greater risk of developing gestational diabetes (Boomsma, 2006).

What treatments might help me?

Despite the increased difficulties in getting pregnant, the good news is that at least 60% of women with PCOS are able to conceive within a year (Brassard, 2008). There are a variety of treatment options which may help to optimize your chances of a “take home baby.”

Modest weight loss

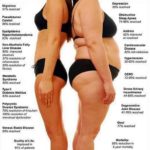

In one study of 263 women with PCOS, those who were overweight (e.g., BMI of 25 or more) had more irregular menstruations than those who weighed less (Kiddy, 1990). This fact correlates with the known improvement in fertility seen when women with PCOS lose weight. While I usually suggest to women that a loss of 15% of current weight will improve ovulation functions, there are studies which have found benefit in losing only 5-10% of current body weight.

One small study, which utilized six months of diet and exercise, found that a majority of subjects resumed ovulating with only 2-5% of body weight reduction (Huber-Buchholz, 1999). Twelve of thirteen non-ovulatory, obese women were able to restore ovulations when the average weight loss was only 14 pounds. This was achieved with six months of gradual dietary changes and regular exercise (Clark, 1995). In a German study 29% of obese, non-ovulating women conceived after a mean weight loss of 22.5 pounds (Hollmann, 1996). By contrast, rapid weight loss (9% weight loss over 6 weeks) was found to impair fertilization rates in obese women undergoing in vitro fertilization (Tsagareli, 2006).

The exercise program successfully used by Clark (1995) included one hour twice weekly of a low impact aerobics group session coupled with one hour twice a week of exercise of the woman’s choice. There is apparently no specific inhibition preventing those with PCOS from exercising. Thompson and colleagues (2009) compared heavyset women with and without PCOS for both muscles strength and aerobic capacity. Women with PCOS were able to exercise to the same extent as a weight matched control group.

Based on the studies of weight loss and return of ovulation, the most recent consensus statement from the Androgen Excess and PCOS Society (Moran, 2009) states, “Lifestyle management should be used as the primary therapy in overweight and obese women with PCOS for the treatment of metabolic complications. For reproductive abnormalities, lifestyle modification may improve ovulatory function and pregnancy.” In the event that moderate weight loss does not yield your desired pregnancy, medications may be utilized.

Clomiphene citrate (“Clomid”)

For women with PCOS, Clomid is the recommended first choice of drug treatments to induce ovulations (Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM). Clomid pills are given for only five days following a menstrual period. For example this could be cycle days 5 through 9 after either a “natural bleed” or one induced by taking progesterone. Clomid is believed to induce ovulations by increasing levels of FSH. Among women with PCOS utilizing Clomid, ovulation rates are about 75% with single babies born to 25% of those (Homburg, 2005).

Metformin (“Glucophage”)

Many overweight women with PCOS have “insulin resistance (IR).” IR means that the liver and muscles do not respond to the normal amounts of insulin produced. This in turn can force the pancreas to create ever higher amounts of insulin. Metformin is one of the most common insulin sensitizing medications used in both type 2 diabetics and PCOS. It lowers fasting insulin levels which can lower levels of male hormones, and may increase incidence ovulations.

The utility of metformin as a method of inducing ovulations is being re-evaluated. One hundred and fourteen women with PCOS were randomly assigned to either metformin or a placebo pill paired with a diet and exercise program. After six months there were no differences in rates of ovulation between the two groups (Ladson, 2010).

In a much larger study of 626 infertile women with PCOS, Dr. Richard Legro (2007) and fellow researchers compared metformin to Clomid to a combination of both medications for pregnancy rates. The live birth rate for metformin alone was 7.2%, 22.5% for Clomid alone, and 26.8% for the metformin plus Clomid group. Despite the increase of 4% there was no statistically significant advantage for adding metformin to Clomid.

Laproscopic Ovarian Surgery

For women who do not respond to Clomid, a surgery on the ovaries may be helpful. Laproscopic ovarian surgery (LOS) utilizes a laser or cautery device to put four to ten punctures in the ovary. Nicknamed the “whiffle ball” procedure, these small holes drilled in the surface of the ovary decrease the excessive amounts of LH produced by a polycystic ovary. About 50% of women receiving this treatment will ovulate, the remainder may need other infertility medications (Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM).

When 282 women with PCOS were randomly assigned to LOS or Clomid plus metformin, pregnancy rates after six months were similar (15-17%). Yet there were four twin pregnancies in the Clomid plus metformin group (Abu Hashim, 2010). Given that all the women in this study did not respond to Clomid initially, the take home message is that pregnancy can be achieved with the use of another treatment.

In summary,

PCOS can be defined by the medical profession in a number of ways. Yet one of the defining characteristics is known to be erratic or missed menstrual periods — which usually means missed ovulations. If you have been having a hard time getting pregnant, ovulation problems caused by PCOS may be the reason. Should this be true, there are things you can do on your own such as modest weight loss through better diet and four hours of exercise a week. After six to twelve months of trying on your own, it is time to see a GYN or clinic to consider a trial of medications.

Trying to get pregnant? Well this might help, check it out here

Here are some additional sources of information which may be helpful to you:

Tackle The Root Cause Of PCOS

WebMD Video: Getting Pregnant with PCOS

WomensHealth.gov – Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

PCOSupport

Special thanks to the Author of this article

Jane Harrison-Hohner, RN, RNP

Pleased I noticed this to be honest. I’m liking your content buddy.

We appreciate your this page. Anticipating reading a lot more of your posts. I really hope to give something back and support other people like you helped me.